|

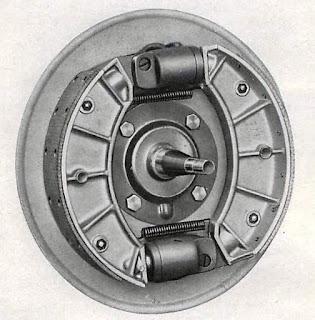

The Alfatross is marking its territory. How do you

determine the severity of a leak from its puddles? |

They both have leaks!

|

Engine oil leak fluorescing under ultraviolet light showing that the

leak is between the pan and the sump. |

The Alfatross has several circulatory systems for its various fluids: coolant that circulates between the radiator, engine, and heater; oil circulating throughout the engine from the oil pan to the oil pump to the cylinder heads, camshafts, crankshaft, and piston rings; fuel that has to move from the gas tank to the electric fuel pump to the mechanical fuel pump to the carburetors; brake fluid that moves from the reservoir to the master cylinder to the wheel cylinders and part way back; steering gear fluid inside the steering box; hypoid gear oil inside the differential; and even another type of oil splashing around inside the transmission.

It seems that all those different fluids just can't wait to escape and are looking for opportunities at every turn. It isn't easy to keep them in captivity. Because they are relentlessly stored, released, heated, cooled, compressed, decompressed and recycled while doing their jobs, they have to pass through tubes, chambers, reservoirs, pumps, valves, and sumps made from different materials with different expansion and contraction coefficients--all grudgingly held together with different types of seals and gaskets. It's not an easy life.

|

Minor leak from a crack at the engine oil temperature port

in the back of the sump. |

We tend to forget this because automotive engineers have virtually eliminated engine oil leaks in modern cars, but things were different when The Alfatross was born 62 years ago. Oil and fluid leaks were more or less expected and not cause for alarm. I was reminded of this recently during correspondence with members of the "Alfa 1900 Brain Trust". After determining that The Alfatross has an engine oil leak somewhere between the pressed steel oil pan and the sump, as well as a crack just below the oil temperature sensor port in the sump, I sent out a plaintive query asking what could be done to fix them short of pulling the engine. The responses were as bleak as they were historically enlightening:

Joost Gompels (gallows humor): My

car leaked oil. I thought it was the oil temp sensor at the back of the oil pan

and the gear box from a bad shaft seal as it got less as the oil level fell.

Possibly hairline cracks in the casing. I

found it hard to seal the cam rocker covers because of the locator pins,

warpage and overtightening. Thought

we all subscribed to the wisecrack that if an Alfa did not leak--it had run

out of oil!

Peter Marshall (look on the bright side): I duuno! I always thought that the Austin 7 survived well because the chassis accumulated a little oil rather than rust. I have never looked that hard at whether 1900s drip much.

Giuseppe Maranghi (careful how you treat it!): As all pre-Fiat Alfas have a generous oil pump, both in

pressure and quantity, NEVER run at hi revs a cold Alfa engine, otherwise the

cold oil, supported by the generous pressure, will find by itself more than one

way to "escape" out of the block. Did You all know that Motorway Police Giulia SW had a sort

of heating plugs, like those for diesel engines, to keep the engine properly

warmed in case of emergency?

Dan Allen (just cowboy up and fix it!): Steel is more susceptible to vibration cracks especially

around fittings and seams. I think

anyway. Also Don, it is very unlikely

the engineers design an engine with thought of future R&R [in response to my observation that you can't remove the oil pan and sump without removing the engine]. Generally Alfa liked to put the engine and

trans together for installation and most likely would recommend the same if

they needed to come out. [meaning that I would have to remove both the engine and the transmission just to seal a leak in the oil pan!]

Joost (Oh those pesky Russians!): One

cannot generalize too well. There are many different types of steel and alum

alloys. Take an aircraft and a bridge for example. One is aluminum and the

other steel almost exclusively yet both flex and vibrate in service not to

mention expansion and contraction. Giuseppe

may wish to comment on this that Italy after WWII had to import low quality

Russian steel while able to manufacture aluminum itself. So it's choice of

materials might be governed by other factors. Basically

aluminum is a better heat conductor and its bigger mass and the ability to

easily cast fins on its outer surfaces lets it dissipate heat from the oil pan

better than a steel one.

Giuseppe ("Stalin", in Russian, means "made with steel"): Well, it's not a comment, it's History, but nobody will find

it in Italian books: When Fiat decided for a joint-venture with Stalin

"and company", the payback was not Russian "rubles", but full-of-sulphur (and maybe something else!) Russian steel, hence

those 127s, 131s, Lancia Betas, Alfettas, Alfa6s and, above all, Alfasuds,

carved like Swiss cheese. Italy, having the biggest communist party in the western block, even supporting Red Brigades, and all big factories in need of steel--Alfa Romeo included--had to buy Russian one, just to keep the political situation quiet.

Leaks--how much is too much?

|

| 5 ml of engine oil isn't much! |

By modern standards, any leak is too much. By 1955 standards a small leak is nothing to be concerned about, but at what point should you start to worry? One slow afternoon I did an admittedly sketchy experiment to figure out how much engine oil The Alfatross is losing over time. Because the drops from the leaks were landing in different places under the car I could not easily measure the volume of leakage, but I could measure the size of the puddles and compare them with surrogate puddles made from precise amounts of oil created elsewhere on the shop floor. I filled a syringe with 1, 2, and 5 ml amounts of the same kind of oil in the crankcase, squirted them on the floor, then waited a couple of days to see how much area they spread out to cover. To my surprise, the three samples spread out and joined up to create a puddle about 9 inches (23 cm) across. I estimated a puddle that size would represent at least a couple of week's worth of leakage. If The Alfatross' crankcase holds about 8 quarts of oil and there are 946.353 ml in a quart, there are 7,570 ml of oil in a full crankcase. Assuming a steady rate of leakage of 0.57 ml/day it would take about 1,887.6 weeks, or about 36.3 years to drain the crankcase!

|

Individual puddles created by 5, 2 and 1 ml

"drips" before spreading out. Scale is in

cm. |

|

The puddles spread out to form a single

puddle estimated at about 9 inches or 23 cm

across. Roughly 2 weeks worth of leakage. |

So call me obsessive, but that's too much!