By now there must be some people out there wondering "If it was good enough to place third in the "Coachwork by Zagato" class at the Arizona Concours d'Elegance in January, why are you still working on The Alfatross?" My excuse is that it really doesn't take that much to put a car on the lawn: If it is a rare "Italian Exotic", runs well enough to cover a mile or two, has a shiny new coat of paint, fresh upholstery, and been under the same ownership for the last 47 years--that's good enough. But not as good as it can be. What we're doing now is making The Alfatross as good as it can be, and that takes a lot more work.

1. They never fit in the first place (quality control didn't exist in 1955),

2. Original parts that did fit originally got bent, worn, or corroded over the last 61 years (imagine that!), and

3. The process of restoration interfered with the original fit (unintended consequences).

Bad decision. I should have just replaced all the lines and connections with new ones. After installing the original line from the master cylinder to the rear axle--the longest brake line on the car--it leaked, necessitating cleaning up a big mess, making another line, and buying two more bottles of fluid!

YnZ's harness came with numbered wires and 3 sheets of instructions describing what the wires connected to, but there were problems, including the fact that some of the wires mentioned in the instructions didn't exist. Fortunately, I also had the Alfa factory wiring schematics and a beautiful set of 9 drawings by Hans Josefsson, (owner of chassis 01977) segregating the circuits by function (starting, charging, lights, signalling, service, etc.).

So rewiring The Alfatross should be a slam dunk . . . except that the schematics don't agree on a lot of important details. Add to that the fact that the Alfatross has some extra circuits not mentioned in any of the schematics. Given the simplicity of the car's electrical system, none of this is a big problem, it just means that some circuits have to be modified, eliminated, or added. And that takes a lot of time.

The answer to the question of why is it taking so long is that putting a 61 year-old, hand-made, unique Italian Exotic back together is not like putting a new, mass-produced, cloned, modern car together. There's a surprise around every corner. How long is it supposed to take? Nobody knows. They're all different . . . .

Who Knows Where the Time Goes?

I do, at least when it comes to the restoration of this particular vehicle! The superb paint and bodywork done by Tim Marinos of Vintage Autocraft was finished 8 months ago. The excellent interior work done by Derrick Dunbar at Paul Russell and Co. was finished 6 months ago. We got the engine back from DeWayne Samuels at Samuels Speed Technologies 4 months ago. Those three operations probably consumed on the order of 3,000 hours of other people's time and the results were well worth it. Ever since the body, interior, and engine were reunited at The Shed in January it has been up to us to get all those elements to fit together, and it hasn't been easy. Many of the things we did to get the car ready for the Arizona Concours have been undone and redone several times to achieve a better fit and finish.Why Things Don't Fit

It appears that there are at least three different reasons why, even after a careful restoration, things don't fit:1. They never fit in the first place (quality control didn't exist in 1955),

2. Original parts that did fit originally got bent, worn, or corroded over the last 61 years (imagine that!), and

3. The process of restoration interfered with the original fit (unintended consequences).

Welcome to My World

Here are three examples of where the time goes as a result of things not fitting:Switches

The Alfatross has 6 toggle switches mounted under the dash where it turns from vertical to horizontal. Four of them fit so that the toggles are oriented to be "on" when their toggles are in the "up" position. The mounting holes for the other two switches were drilled a couple of millimeters too close to the upward turning lip at the back of the dashboard so they sit cockeyed and look glaringly "wrong". This was the way they came from the Zagato factory. For the Arizona Concours we reinstalled them crooked to save time. Now that we are taking the time to do things right, I shaved a couple of millimeters off the backs of the two recalcitrant switches to make them fit the way they were supposed to 61 years ago. I don't think Ugo Zagato would disapprove.Brake Lines

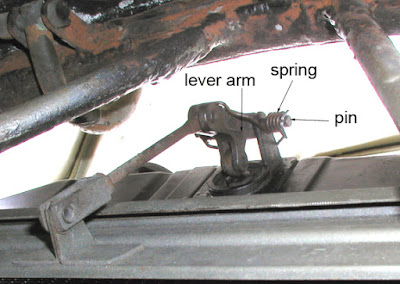

The Alfatross was taken off the road in 1971 when one of the metal brake lines rusted through and let all the fluid out. But the rest of the lines looked good after cleaning them inside and out and re-tapping the old flare connections. Deducing that it would be faster and more authentic to reuse as many of the old brake lines and flare connections as possible, I decided to replace all the small metal brake lines on the backs of the front wheels and on top of the rear axle, but to keep the larger diameter lines from the reservoir to the master cylinder and from the master cylinder to the front wheels and rear axle. |

| Bad decision: This tiny hole in the longest brake line on the car resulted in hours of additional, unnecessary work. |

Bad decision. I should have just replaced all the lines and connections with new ones. After installing the original line from the master cylinder to the rear axle--the longest brake line on the car--it leaked, necessitating cleaning up a big mess, making another line, and buying two more bottles of fluid!

|

| It's the little things: The dash warning light that indicates the heater fan is operating did not work until I realized that paint was keeping its housing from grounding inside the hole it fits into. |

Electrical Gremlins

The Alfatross has a new electrical harness made by YnZ Yesterday's Parts. It is supposedly a copy of the original harness which I removed and sent to them. Even though The Alfatross' electrical system is about as simple as one can get, wires can get crossed, labels can fall off, and ground wires can fail to make contact with the chassis due to the buildup of primer and paint. Getting the wiring right can be a hit-or-miss proposition.YnZ's harness came with numbered wires and 3 sheets of instructions describing what the wires connected to, but there were problems, including the fact that some of the wires mentioned in the instructions didn't exist. Fortunately, I also had the Alfa factory wiring schematics and a beautiful set of 9 drawings by Hans Josefsson, (owner of chassis 01977) segregating the circuits by function (starting, charging, lights, signalling, service, etc.).

So rewiring The Alfatross should be a slam dunk . . . except that the schematics don't agree on a lot of important details. Add to that the fact that the Alfatross has some extra circuits not mentioned in any of the schematics. Given the simplicity of the car's electrical system, none of this is a big problem, it just means that some circuits have to be modified, eliminated, or added. And that takes a lot of time.

|

| The simple drawing accompanying YnZ 's replicated wiring harness shows wires that don't exist in the instructions and the instructions mention wires and connections that don't show in the drawing.! |