Read All About It!

|

| No. 01845, as featured in the latest issue of Octane Magazine |

The recent exhumation of Alfa Romeo 1900C SSZagato chassis No. 01845 caused quite a stir in the classic car press. The May issue of

Octane magazine contains a 9-page article titled "Buried Treasure" about one of The Alfatross' brethren, No. 01845, built in 1954. Under the News section of the alfa1900 Web site you can find both a newspaper article and a series of photos showing it being removed from its tomb of 40 years:

http://www.alfa1900.com/photobase2/car_pages/01845/index.html.

|

Built a few months before The Alfatross, 01845's interior is quite different,

with a flat-top dash, factory wheel, and plush seats. Octane. |

|

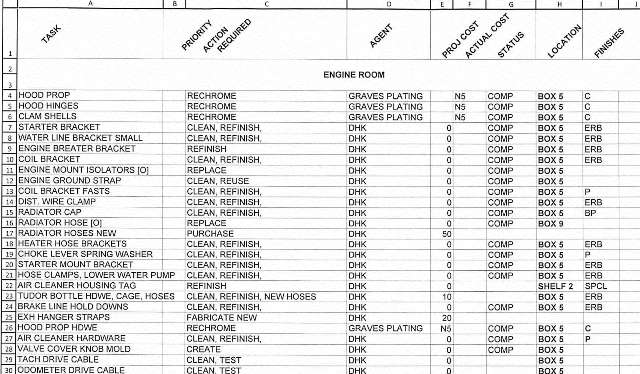

O1845's engine room appears to be identical to the Alfatross'. Reportedly,

after changing the oil and gas and attaching a fresh battery, it started and

ran! Octane. |

Z inderella

Painted green, originally, with a light blue interior, No. 01845's history is very much like the Alfatross'. The first owner was Signor Ruggero Ricci of Lucca, about whom almost nothing is known. After only a few months Ricci sold it to his friend Otello Biagiotti, who was something of a racer. The car changed hands 5 more times before ending up in the possession of Signor Strippoli in 1969. Like Cinderella of fairytale fame, No. 01845 was consigned to a dark dungeon for most of its life--unknown, unloved, unseen for more than 40 years . . . until being rescued by Signor Corrado Lopresto, an Alfa collector, who recognized its deeper beauty--and value--in spite of its outward rough and dirty appearance.

|

| Corrado Lopresto with No. 01845, in storage for more than 40 years! Like me, the previous owner of 01845 bought it in 1969 and held on to it for more than 40 years. Sr. Lopresto is 01845's eighth owner. I am the Alfatross's seventh owner. www.alfa1900.com. |

So Where's the Treasure?

For most people "treasure" equals precious metals and jewels--things you can sell imediately. When you add "buried" in front of "treasure" it conjures up an even more romantic image usually involving pirates, maps with X marking the spot, a certain amount of personal risk, and a great reward far exceeding the time and energy expended to get it. Because my wife and I are marine archaeologists, people always ask, "Have you found any treasure?" Unless you equate "history" with "treasure" the answer is always "No".

Signor Lopresto stated that he has no intention of restoring No. 01845. In fact, it is now presented in "as found" condition in a special Italian Cars exhibition at the Louwman Museum in The Hague. To the average person, No. 01845 looks like it was "buried" alright, but "treasure"? How so? What can you do with it? Show car? Maybe on Halloween. Reliable transportation? Not hardly. What about all the rotting tires, rubber water hoses, brake lines, weatherstripping, seals, electrical wiring, gaskets, and grommets? What about all the peeling paint, dents, rust, foggy windows, creaking hinges?

Octane Supplement

What sorts of things are "valuable" in today's world? Real estate, precious metals and gems, equities, bonds--and collectibles. Cars like No. 01845 are sought after by collectors, not normal people looking for safe, reliable, good-looking transportation. So you have to understand car collecting as a phenomenon.

A good place to start is the 19-page Special Supplement in the same issue of

Octane, "Building a Classic Car Collection from the Modest to the Magnificent." Significantly, the supplement seems to be sponsored by the international bank Credit Suisse. It is pretty comprehensive in a "Cliff'sNotes" sort of way. The several articles in this supplement help to explain why No. 01845 is considered "treasure" in certain, rarefied circles:

Under

Why Collect? we have the simple explanation "You can't drive a house or a shares portfolio, so utilizing spare cash to build an interesting car collection makes a lot of sense." Particularly when you look at how much certain cars--but by no means all--have appreciated over time. Example: a 1966 Ferrari 275 GTB that sold at auction in 1996 for $199,000 sold last year for $2,365,000!

The

What to Collect? section boils down to whatever appeals to you and your idea of what constitutes a collection.

|

The restored 1955 Lancia Aurelia B24S Spider America: $825,000. Sports Car

Market. |

|

The "preservation" 1955 Lancia Aurelia B24S Spider America: $805,000.

Sports Car Market. |

Original or Restored? Originality is the buzz word these days. Original paint, original interior, original cigarette butts in the ash tray, original dirt in the wheel wells, original dents, chips, and scratches, original gas in the tank and water in the radiator. Like paintings by the Old Masters or Greek sculptures, old, original cars are supposed to be "preserved" in their original condition, not restored to their former glory. The word "stewardship" is replacing "ownership" in the car collecting world, and the vehicles are being looked at as important historical objects that just happen to be cars.

In last month's issue of

Sports Car Market magazine there was an excellent example of how powerful the "preserved" vs. "restored" factor is in car collecting. Two highly-desirable 1955 Lancia Aurelias were sold in February in auctions in Phoenix and Scottsdale one day apart. The "restored" blue car went for "825,000 while the "preserved" red car with its dents, rust, scratches, tattered upholstery went for almost the same price: $805,000!

Buying Trends in car collecting are ever-changing and largely unpredictable. My impression is that most collectors acquire cars that they like, for whatever reason, and hope that their "value" will increase over time. A natural conclusion is that collectors will be most interested in cars that they always admired but could not afford until later in life. This observation may explain why cars from the 1950s and '60s are so valuable now. But will they decline in value as the Baby Boomer generation passes? Does their "value" have a shelf life?

The exhumation of No. 01845 is an important event for The Alfatross. It brings another member of the family out of obscurity and into the limelight. As one of very few "unmolested" examples, it provides verification of additional original construction details. And its change of ownership provides a strong vote by a major collector in favor of "preservation" over "restoration." I have to admit that if I were the new owner of 01845 I would probably do the same thing--it would sure be a lot easier and cheaper!-- but because it has already been disassembled, the Alfatross is not a preservation candidate and so it continues on the path to historically sympathetic restoration.

|

| 01845--an example of the "preservation" trend in car collecting. Octane. |